Jerome Jacobson and his network of mobsters, psychics, strip club owners, and drug traffickers won almost every prize for 12 years, until the FBI launched Operation ‘Final Answer.’

On August 3, 2001, a McDonald’s film crew arrived in the bustling beach town of Westerly, Rhode Island. They carried their cameras and a giant cashier’s check to a row of townhouses, and knocked on the door of Michael Hoover. The 56-year-old bachelor had called a McDonald’s hotline to say he’d won their Monopoly competition. Since 1987, McDonald’s customers had feverishly collected Monopoly game pieces attached to drink cups, french fry packets and advertising inserts in magazines. By completing groups of properties like Baltic and Mediterranean Avenues, players won cash or a Sega Game Gear, while “Instant Win” game pieces scored a free Filet-O-Fish or a Jamaican vacation. But Hoover, a casino pit boss who had recently filed for bankruptcy, claimed he’d won the grand prize–$1 million dollars.

Like winning the Powerball, the odds of Hoover’s win were 1 in 250 million. There were two ways to win the Monopoly grand prize: find the “Instant Win” game piece like Hoover, or match Park Place with the elusive Boardwalk to choose between a heavily-taxed lump sum or $50,000 checks every year for 20 years. Just like the Monopoly board game, which was invented as a warning about the destructive nature of greed, players traded game pieces to win, or outbid each other on eBay. Armed robbers even held up restaurants demanding Monopoly tickets. “Don’t go to jail! Go to McDonald’s and play Monopoly for real!” cried Rich Uncle Pennybags, the game’s mustachioed mascot, on TV commercials that sent customers flocking to buy more food. Monopoly quickly became the company’s most lucrative marketing device since the Happy Meal.

Inside Hoover’s home, Amy Murray, a loyal McDonald’s spokesperson, encouraged him to tell the camera about the luckiest moment of his life. Nervously clutching his massive check, Hoover said he’d fallen asleep on the beach. When he bent over to wash off the sand, his People magazine fell into the sea. He bought another copy from a grocery store, he said, and inside was an advertising insert with the “Instant Win” game piece. The camera crew listened patiently to his rambling story, silently recognizing the inconsequential details found in stories told by liars. They suspected that Hoover was not a lucky winner, but part of a major criminal conspiracy to defraud the fast food chain of millions of dollars. The two men behind the camera were not from McDonald’s. They were undercover agents from the FBI.

This was a McSting.

At the FBI’s Jacksonville Field Office in Florida, Special Agent Richard Dent added the Hoover videotape to his growing pile of evidence. Sandy-haired and highly-organized, Dent was a 13-year veteran of the Bureau, who spent his days investigating public corruption and bank fraud. But in the last 12 months his desk had filled with fast food paraphernalia. Leaflets for “Pick Your Prize Monopoly” and “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?” described McDonald’s games played in 14 countries. He read small print that revealed how the odds were stacked against the customer: McDonald’s makes one piece from each set of properties extremely rare, so while thousands have three of the four railroads, the odds of pulling the Short Line Railroad—and winning a PT Cruiser—were 1 in 150 million.

Dent’s investigation had started in 2000, when a mysterious informant called the FBI and claimed that McDonald’s games had been rigged by an insider known as “Uncle Jerry.” The person revealed that “winners” paid Uncle Jerry for stolen game pieces in various ways. The $1 million winners, for example, passed the first $50,000 installment to Uncle Jerry in cash. Sometimes Uncle Jerry would demand cash up front, requiring winners to mortgage their homes to come up with the money. According to the informant, members of one close-knit family in Jacksonville had claimed three $1 million dollar prizes and a Dodge Viper.

When Dent alerted the McDonald’s headquarters in Oak Brook, Illinois, executives were deeply concerned. The company’s top lawyers pledged to help the FBI, and faxed Dent a list of past winners. They explained that their game pieces were produced by a Los Angeles company, Simon Marketing, and printed by Dittler Brothers in Oakwood, Georgia, a firm trusted with printing U.S. mail stamps and lotto scratch-offs. The person in charge of the game pieces was Simon’s director of security, Jerry Jacobson.

Dent thought he had found his man. But after installing a wiretap on Jacobson’s phone, he realized that his tip had led to a super-sized conspiracy. Jacobson was the head of a sprawling network of mobsters, psychics, strip club owners, convicts, drug traffickers, and even a family of Mormons, who had falsely claimed more than $24 million in cash and prizes. But who among them had betrayed Jacobson, and why? Dent knew agents had to move carefully. If they apprehended a “winner” too soon, he or she might alert other members of the conspiracy who would destroy evidence, or flee. With the scheme still in full-swing, the FBI needed to team up with McDonald’s to catch Uncle Jerry and his crew red-handed.

JEROME PAUL JACOBSON always dreamed of becoming a police officer. He was born in 1943, in Youngstown, Ohio, and moved to Miami, Florida, as a teenager. Chronic allergies and a series of unlucky injuries always seemed to ruin his ambitions, like when he applied for the Marines, but was discharged from basic training with high arches. In 1976 he was sworn in to Florida’s Hollywood Police Department, but just a year later he injured his wrist in an altercation. During a prolonged medical leave, in 1980, Jacobson collapsed with a severe paralysis in his arms, legs, eyes and respiratory system. Doctors diagnosed a rare neurological disorder, and Jacobson’s police officer wife, Marsha, took a leave of absence to care for him. “I became his private nurse, I bathed him… massaged his muscles, fed him,” she recalled. With Jacobson unfit to return to work, the city terminated him. By 1981 the couple had moved to Atlanta, Georgia, where Jacobson recovered enough to work as a mechanic, building alternators for cars he couldn’t afford.

Luckily, Marsha was offered a job as a security auditor for the accounting firm Arthur Young, and was assigned to one of their clients, Dittler Brothers. In 1981, she recommended her husband for a job there too, but the couple constantly argued at work, and by 1983 they had divorced. Finding his feet in private security, Jacobson started to climb the ranks until he oversaw all production for Dittler’s client, Simon Marketing, and their $500 million McDonald’s account.

When Jacobson marched through the printing works, with his slicked-back hair and a little paunch that overhung his belt, he looked every part the ex-cop. He was quick with a joke, but commanded respect for his hard work and obsession with loss-prevention. “He inspected workers’ shoes to check they weren’t stealing McDonald’s game pieces,” one colleague told me, while a truck driver who transported game pieces recalled: “I couldn’t even go to the bathroom without someone going with me.” Impressed by Jacobson’s attentioned to detail and police credentials, in 1988 Simon Marketing poached him.

“It was my responsibility to keep the integrity of the game and get those winners to the public,” Jacobson would later tell

Before each bi-annual game, Jacobson arrived at the drab Dittler Brothers’ office at 5 a.m to observe their Omega III supercomputer making the McDonald’s prize draw. He watched the printing presses that roared for 24 hours a day for three months, using 100 railroad cars of paper to print half a billion game pieces. Laid end-to-end, the paper tickets would stretch from New York to Sydney–nearly two tickets for every American. Jacobson observed technicians applying the “INSTANT WINNER!” stamp to blank game pieces, and pioneered random watermarks that deterred counterfeiters. He locked the winning pieces in a vault behind coded keypads and dual-entry combination locks. It was Jacobson who personally scissored out the high-value game pieces and slipped them into envelopes, before sealing each corner with a tamper-proof metallic sticker. In a secret vest, of his invention, Jacobson transported the winning pieces to McDonald’s packaging factories across the country.

Everything he did was overseen by an independent auditor. On flights she sat in coach, while Jacobson flew first class, where he tried to impress other passengers by flashing his old police badge. On one flight, Jacobson and another security manager sent an air steward back to show the accountant the empty liquor bottles they’d guzzled. When they arrived at the factory, Jacobson would summon a forklift of french fry containers, hide the winning game piece, and send it into the wild. Then he liked to hit a Ruth’s Chris steakhouse and order “everything”–more than he could eat, and charge it to his expense account.

The 1980s was America’s “decade of greed,” and it was Jacobson’s job to create instant millionaires. Playing God was intoxicating, as was holding a stranger’s fate in the palm of his hands. Female employees among the 30 staff he controlled complained that he criticized how they dressed, and he often wrote up workers for mistakes. Jacobson’s $70,000 salary was six times his police officer’s pay, and he was obsessed with achieving the gold medallion airline status, sometimes flying to factories via several cities to accrue airline points, to the irritation of those who had to shadow him.

Jacobson was also deep into his own get-rich-quick scheme. He boasted to colleagues that he was waiting to collect his “riches” from a mysterious “investment.” All he needed was to find 10 more people to sign up and invest. “A psychic had told him to invest money and he would be richly rewarded,” one former colleague told me. But they believed he’d invested in a Ponzi scheme. One colleague told me Jacobson swore by the advice of a local fortune teller, and often excused himself from work, saying: “I think she needs to tell me something.”

This was the man entrusted with creating a theft-proof system for one of America’s largest corporations. It was a thrill to protect the Monopoly promotion, and only a natural part of his job to consider the system’s fallibilities. But soon the temptation to steal had become irresistible.

One day in 1989, at a family gathering in Miami, Jacobson slipped his step-brother, Marvin Braun, a game piece worth $25,000. “I don’t know if I just wanted to show him I could do something, or bragging,” Jacobson later admitted, but he just needed “to see if I could do it.” When his local butcher in Atlanta heard that Jacobson was in charge of the McDonald’s Monopoly prizes, he said he’d like to win a prize. Jacobson boasted that he could make it happen, but it would look too suspicious because they were friends and neighbors. The butcher offered to find a distant friend to claim a $10,000 prize, and gave Jacobson $2,000 for the stolen ticket. It was easy money.

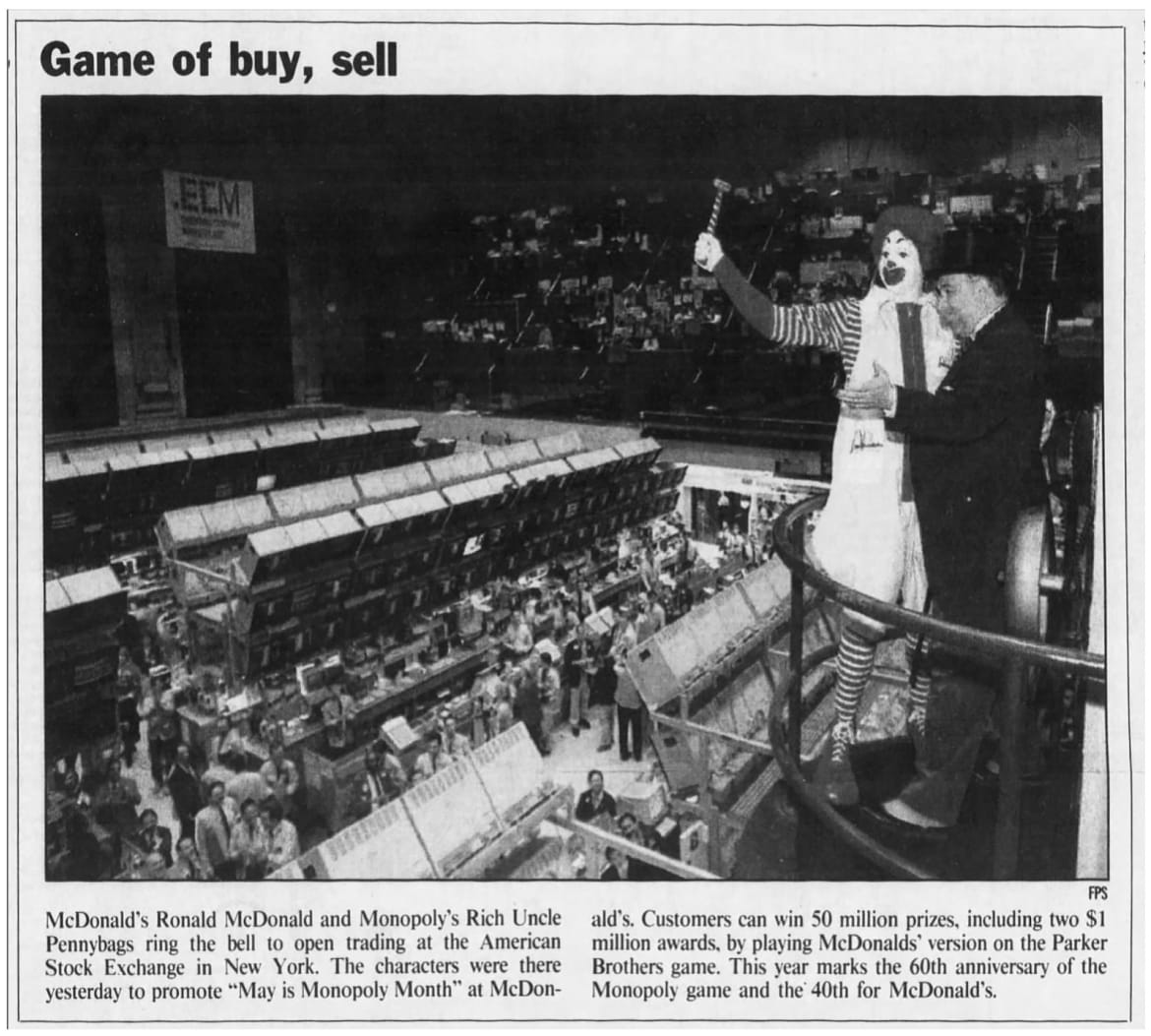

McDonald’s was already overwhelmed with employee theft. In Sheboygan, Wisconsin, a 17-year-old restaurant employee was arrested for stealing 3,000 Monopoly game pieces. In response, McDonald’s started handing out game pieces from a secure roll at the counter. As a result, Jacobson was removed from the “seeding” process for several years. But in 1995, as McDonald’s ramped up the scale of the promotion, game pieces were ‘blown’ onto soft drink cups and hash brown wrappers. That year, Ronald McDonald and Monopoly’s Rich Uncle Pennybags rang the opening bell on Wall Street, and Jacobson found himself back in charge of distributing the game pieces.

During that 1995 prize draw, something happened that would change the game. According to Jacobson, when the computerized prize draw selected a factory location in Canada, Simon Marketing executives re-ran the program until it chose an area in the USA. Jacobson claimed he was ordered to ensure that no high-level prizes ever reached the Great White North. “I knew what we were doing in Canada was wrong,” Jacobson recalled. “Sooner or later somebody was going to be asking questions about why there were no winners in Canada.” Believing the game was rigged, he decided to cash in too.

Not long afterward, Jacobson opened a package sent to him by mistake from a supplier in Hong Kong. Inside he found a set of the anti-tamper seals for the game piece envelopes—the only thing he needed to steal game pieces en route to the factory. “I would go into the men’s room of the airport,” he later admitted, the only place the female auditor couldn’t follow him. “I would go into a stall. I would take the seal off.” Then he’d pour the winning game pieces into his hand, replace them with “commons,” and re-seal the envelope. First, he stole a $1 million “Instant Win” game piece and locked it in a safety deposit box. Then he stole documents that he claimed proved the Canada conspiracy. “I thought I would need that to protect myself,” Jacobson recalled. If his employer ever fired him, he had a “get out of jail free” card. But when he stole another $1 million game piece, Jacobson did something awesome.

On November 12, 1995, a donations clerk at the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Tennessee ripped open the morning’s mail, and discovered a brightly colored card. At first, Tammie Murphy assumed it was junk mail, until she noticed the tiny Monopoly game piece inside. McDonald’s officials descended on the hospital and examined the game piece under a jeweler’s eyepiece. Ronald McDonald himself attended a press conference, where the hospital was announced the $1 million winner. Despite an investigation, the New York Times could not uncover the identity of the generous donor.

Back in Atlanta, Jacobson’s butcher was ready for another win. This time, he proposed that he’d travel with his sister to Maryland where she would “find” the lucky game piece on a box of fries. Jacobson gave the butcher a stolen game piece worth $200,000 in exchange for $45,000 of the winnings. “I figured I could trust him because he paid me the first time,” Jacobson recalled. But the butcher double-crossed him in Maryland and claimed the prize himself. All Jacobson got was $4,000, and a big surprise. One evening, Jacobson was watching television when he saw a commercial for the McDonald’s Monopoly game. To his complete disbelief he watched his butcher celebrating his big win. He reached for the phone.

“You live here,” Jacobson protested. “You know me.”

>

LOTTERIES AND SWEEPSTAKES have been mired in corruption since biblical times, when lots were drawn to read the will of God. But it was the Medieval Italians who first used prize drawings as a sales promotion. In 1522, a Venetian man was condemned to death after tampering with the prize draw for 1,500 golden ducats, a parcel of silk and a live wild cat. Allegations of fraud and abuse shuttered an English lottery in 1621, which funded America’s earliest colonies. In the New World, centuries of sweepstake chicanery followed, until 1890 when lotteries were banned in every state except Delaware and Louisiana. This ushered in an era of promotional “contests” in which marketers could avoid prosecution by making no purchase necessary. Today, you can enter a McDonald’s contest without buying a burger—just write in for a free ticket and take your chances.

It was by chance that Jacobson met the man who would industrialize his Monopoly scam. Jacobson was sitting in Atlanta’s airport one day in 1995, when a giant gentleman folded himself into the next seat. Gennaro Colombo, 32, looked like Al Capone, and when Jacobson enquired where he was headed, Colombo unzipped a bulging purse full of $100 bills, and said: “Atlantic City.” Colombo said he was born in Sicily and raised in Brooklyn, New York, before moving to South Carolina, where he operated adult nightclubs, underground casinos and a sports betting ring. He claimed he was a member of New York’s infamous Colombo crime family.

When Jacobson revealed that he worked in promotional gaming, Colombo was intrigued. He enjoyed finding new ways to cheat a system. When Charleston County, Georgia passed new laws restricting where strip clubs could be operated, Colombo opened a house of worship named The Church of Fuzzy Bunnies. “I want them to read the Bible for two hours every night, and then we’ll drink and let the girls dance,” said Colombo, who claimed that God came to him in a dream with the idea. By November of 1995, Jacobson had slipped Colombo a game piece for a brand new Dodge Viper. The Italian, who was obsessed with The Godfather and had ambitions of becoming an actor, agreed to wave a giant car key in a McDonald’s commercial. Instead of the sports car he took the money, his wife, Robin Colombo, told me. “He was a big guy. A Viper? No.”

https://youtu.be/viU25SQFKO8

With a mop of black curly hair and a contagious laugh, Robin, 34, had become engaged to Colombo after a two-week romance. She was thrilled with the trappings of a Mafia wife: bodyguards, chauffeurs, two rottweilers and a last name that commanded fear and respect. By now, Colombo was traveling with friends from Atlanta to Boston, where they’d “win” $1 million prizes, thanks to stolen tickets from Jacobson. Soon Colombo introduced Robin to Jacobson, calling him “Uncle Jerry,” and in 1996, her father, William Fisher, received a stolen $1 million winning ticket. Fisher traveled from his home in Jacksonville, Florida to Litchfield, New Hampshire, to claim his prize, before Robin’s brother-in-law in Virginia became a millionaire too. Every winner sent a kickback in cash via the Colombos to Jacobson.

In 1997, Robin introduced Colombo to her friend Gloria Brown, 37, at an Applebee’s in Jacksonville. “He asked… how much money I could come up with…in order to be eligible,” Brown recalled. A few weeks later, on the side of the I-95 freeway, Brown handed Colombo $40,000 in cash. He showed her a tiny bottle containing the $1 million game piece, dwarfed by his giant hand. “I’ll let you know the rest later,” he mumbled.

Brown traveled to South Carolina to “find” her prize, because too many recent winners now lived in Jacksonville. “It was so secretive,” she recalled. Colombo and a cousin drove Brown to a McDonald’s and parked a safe distance away. They coached Brown what to tell McDonald’s staff, but doubts suddenly consumed her. “I had to just tell, you know, outright lies,” she realized. She thought about running. Do I lose it all or do I keep going? But she did the deed, and afterwards found the two Italians sweating. “They were a little nervous because it took so long,” Brown recalled. They helped her fill out the prize form, writing her name along with the cousin’s South Carolina address. To make it appear like she lived with the cousin, Brown recorded the message on his answering machine, and later told reporters a long-winded story about finding the winning ticket while cleaning out her car.

Robin told me that Uncle Jerry’s money soon funded certain Colombo-run businesses, including a private members’ club in Hilton Head. She thought he was sophisticated and liked the way he dressed. In return, Jacobson sent other “opportunities” to the Colombos, Robin told me. Late one night, she was stoned and rifling through the kitchen for a snack, when she found in their freezer a mysterious plastic bag. Inside was a single gray-colored M&M candy, which was part of a promotional contest, she said. In 1997, the Mars candy company launched a competition to find an “imposter” M&M, along with a game piece that made the winner an instant millionaire. (Mars did not respond to enquiries, but records show that Cyrk, a company that produced promotional materials for Mars, merged with Simon Marketing in 1997.) Colombo suddenly appeared behind her, grabbed the bag and yelled:

“Do not eat this!”

Meanwhile, Jacobson was now living with a huge secret—he had not even told his new wife, Linda, what he was doing. By now he had given his step-brother, Marvin Braun, three more game pieces including one for $1 million. Braun, who owned a chain of maternity clothing stores, claimed he didn’t need the money. “I dropped tickets into Salvation Army tins,” he told me, “Jerry would give me a million dollar ticket… I would give it away… I’ve flushed million dollar tickets down toilets.” By 1998, Jacobson’s nephew, Mark Schwartz, had taken a $200,000 game piece after a meeting in Miami. “I told him what I wanted and the rest was his,” Jacobson recalled. “I wanted $45,000.” At Schwartz’s wedding that year, Jacobson was discussing the Monopoly game when a distant cousin fell into the conversation and also agreed to win a prize. Uncle Jerry’s family tree was sprouting money.

“To make it appear like she lived with the cousin, Brown recorded the message on his answering machine, and later told reporters a long-winded story about finding the winning ticket while cleaning out her car.”

By the end of 1998, Jacobson had become Rich Uncle Pennybags, and America was his game board. He tooled around the United States stealing almost all the big-ticket game pieces, acquiring new properties on a whim, and collecting kickbacks from other players. Now he was hanging out with powerful Italians, he dressed in sharp suits and sometimes used the name “Geraldo Constantino.” He and his wife moved into a fine, red-brick home in Lawrenceville, Georgia, where he tended to its perfect lawn. He purchased a plot of land on Lake Hartwell, a recreation lake on the Georgia border, and paid for expensive cruises, and joined a classic car club. There, he sold one member four game pieces and used the $65,000 to buy a handsome Oldsmobile. Bill LaFoy, who lived opposite Jacobson, lost count of the new cars appearing on the driveway: “I used to kid him about where the winning tickets were,” he said.

After three years married to Colombo, Robin had tired of life as a mobster’s wife. Since the birth of their son, Frankie, her husband seemed to spend all his time at his gentleman’s clubs and casinos. Meanwhile, Robin felt that the Colombos had cut her off from her friends. “They were the type of people who don’t like outsiders,” she said. Lonely and bored, she began confiding in Jacobson during late night phone calls. One night she told him that Colombo was sleeping with her personal trainer. “I was upset about my husband,” she said, “and he goes, ‘Well, you could marry me.’”

“No, I can’t. I’m married,” she said quickly. “I love my husband.”

Robin tried to make her marriage to Colombo work. “He had done some things in Charleston that I freaked out about,” she said, “I told him I needed to get out of South Carolina.” On May 7, 1998, they drove to the Georgia state line to look for land on which to build their dream home. Colombo’s pager had been bleeping all morning, but he ignored it. Robin was behind the wheel of their Ford Explorer as they approached the entrance to the expressway. At the on-ramp, a tractor trailer blocked Robin’s view. When she swung onto the freeway, a speeding F-150 truck smashed into them, dragging their car 250 feet and into a concrete wall. Colombo crawled from the wreckage, but emergency crews had to use the Jaws of Life to cut Robin and her son free.

“The policeman told me he thought I was gonna be the one to die because I was the one covered in blood,” Robin told me. But at the hospital, Colombo’s blood pressure dropped so low they wrapped his body in refrigerated blankets. “My mother-in-law ran over to me and told me she knew this was going to happen,” Robin recalled. “She had a vision in a dream the night before. That’s why she was trying to page him all day.” At his bedside, Robin shook Colombo’s giant arm, and begged him to wake up. “He was my soulmate,” Robin said. But two weeks later the doctors turned off his life support.

The secret of Jacobson’s success was that he recruited his co-conspirators at random, and soon he was looking for a replacement for Colombo. Jacobson was in London with his step-brother Marvin and their wives, waiting to board a Royal Caribbean Cruise ship, when he met Don Hart and his wife. “The six of us were talking, and we found out that Mr. Hart and his wife were from the Atlanta area,” Jacobson recalled. “And they wound up changing tables to eat with us on the cruise.” Hart had sold his trucking company for a small fortune, and still had a network of contacts all over the United States. When Jacobson revealed his scam, Hart, an honest businessman, found it too good to be true. But he agreed to try it, to “see if it worked,” recalled Jacobson. In 1998, one of Hart’s accomplices redeemed a $200,000 game piece. “After that Mr. Hart told me he didn’t want to be involved in handling any game piece tickets or handling any money,” Jacobson said. Instead, he introduced Jacobson to two friends who could find the needy and the greedy.

The first was Richard Couturier, who owned a chain of fried chicken joints. He was fooled into believing he was helping McDonald’s find real winners, because most people threw away their game pieces. “Mr. Jacobson said every time they ran the game and had winners, the sales were up 38 percent,” Couturier said. He mostly recruited random people he met at parties. At Mardi Gras in 1999, Couturier was riding on a float through the streets of New Orleans, tossing beads into the crowd, when he shouted to another reveler: “Would you be interested in being a McDonald’s winner!” Jacobson gave Couturier “around ten” winning pieces, including several for sports cars and two $1 million prizes. “If I bought a piece of property, I would borrow from my home equity and then Mr. Couturier would write a check to my home equity loan,” Jacobson explained.

Then, at a dinner party in Atlanta, Hart introduced Jacobson to Andrew Glomb, a gregarious gambler who lived in a luxury Spanish-style home in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Glomb spent his days partying, or walking his dog through the lime trees that bordered his property, where neighbors all knew of his checkered past. In 1983, Glomb had been convicted of shipping pure cocaine on a Pan American flight from Miami to Dallas. He’d jumped bond and escaped to Europe for 16 months, before completing his 12-year sentence. Glomb mostly gave his winning tickets to old pals from his drug trafficking days. “It was just the excitement, to have the power,” he told me. “Because I like you, I can make you a millionaire.” But Glomb’s winners introduced less salubrious characters to the scheme. In 1999, a million-dollar winner was a man who had pleaded guilty to distributing 400 pounds of cocaine in Pittsburgh, while running a numbers racket from an Italian restaurant.

Glomb said his winners were all destitute: “They were on their ass…they had nothing. I mean, if you could imagine flying across country, giving somebody a million dollars, and I had to pick up the dinner check.” One day, Glomb arrived in Pennsylvania to visit his family, where his cousin picked him up at the airport. The cousin said: “I got to stop at McDonald’s because my kids wanna play this Monopoly game.”

Glomb smiled, and said: “You know, don’t waste your time.”

Across America, McDonald’s customers were becoming frustrated by the Monopoly game. “Are McDonald’s employees keeping game cards to themselves?” asked a concerned citizen in a letter to the Atlanta Constitution. “We’re talking money here,” said another player in North Miami, who paid for a classified advert for the game pieces he couldn’t find. Instead of sticking those game pieces to customer’s soft drink cups and french fry packets, Jacobson sent them all to Andrew Glomb, including eight $1 million winners. “He told me, ‘Don’t talk about this, don’t talk about that,’” Glomb recalled. Paranoid Jacobson now had dozens of prize winners out there, appearing in TV commercials, and arguing with their spouses about the loot. His black hair had turned gray, and he was bothering his psychics about his future. One received a $50,000 game piece in exchange for chiropractic services and fortune telling (“he did both,” Jacobson said.) But the psychic didn’t see how Jacobson’s fate had already been sealed.

Ever since her husband died, Robin Colombo felt uneasy around her in-laws. The Colombos investigated the car crash, she said, suspecting that she might have killed her husband. “My mother-in-law, Ma, she told me, ‘Do you think if we didn’t know it was an accident you’d be sitting here today?’” At her husband’s funeral, Robin said her father-in-law promised to keep the New York side of the family at bay. “In my mind I was thinking, ‘Papa, I’m really not worried about them, I’m worried about you sniping me down, because I was the driver.’” (Speaking in a thick Sicilian accent, Colombo’s mother denied the family were in the Mafia but confirmed they are related to the late Joseph Colombo, former boss of the Colombo crime family.)

Robin had tried to keep up the ‘good life’ but had turned to forgery, insurance and credit card fraud. During one of her brief spells in prison, Robin felt the Colombos were “brainwashing” her own son, and said she didn’t want Frankie to grow up in the mob. She tried to cut herself off from the “the family,” which she said infuriated them. “Frankie [was] their first grandson, and, you know how Sicilians are,” she said. Robin believes it was the Colombos who told the FBI that her father, William Fisher, her cousin, and best friend Gloria Brown had all illegally won McDonald’s prizes. They wanted her in jail, she said, to avenge the death of their son.

“That was their retaliation,” she added.

The tip to the FBI came in March of 2000. Special Agent Dent called Amy Murray, the McDonald’s spokesperson, to say he believed that William Fisher, the $1 million winner of the 1996 “Deluxe Monopoly Game,” was a fraud. Murray was a quick-thinking Midwesterner who had risen through the ranks at McDonald’s, and was often the public face of the company during any drama. She was the “McQueen” of McDonald’s, said Joe Maggard, a disgraced Ronald McDonald actor who was convicted of making harassing phone calls while posing as the clown.

Murray telephoned Fisher at his home in Jacksonville. “[Fisher] told Ms. Murray that he won the prize in Litchfield, New Hampshire, where he was living for a year,” Dent wrote in an affidavit. However, property and electricity records showed that Fisher had lived in Jacksonville all along. “I believe [Fisher] provided false and misleading information to Amy Murray,” wrote Dent. When he asked about Gloria Brown, Murray revealed that she, like Fisher, had re-routed her annual $50,000 checks to Jacksonville.

Dent opened an official investigation, naming it Operation “Final Answer,” after the “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?” McDonald’s game. The operation would involve 25 agents across the country, who tracked 20,000 phone numbers, and recorded 235 cassette tapes of telephone calls. “You work from the outside in,” explained John Hanson, a former FBI Special Agent who specializes in complex fraud schemes. “But you really want the people who devised the idea.” Hanson said the FBI would have investigated the McDonald’s scam just like any boiler room stock fraud or pyramid scheme: by gathering evidence without anyone finding out. Jacobson made this hard by recruiting co-conspirators in person, in remote locations.

https://youtu.be/lIJ81cw6efk

On April 29, 2000, Jacobson was driving through the South Carolina countryside, with the peaks of the Appalachians in his windshield. In the passenger seat was his friend Dwight Baker, a real estate developer who had sold Jacobson his lakeside plot. Baker was a well-respected member of the local Mormon church, and a devoted father-of-five who lived in a split-level house next to hayfields and farmland. He was a charismatic man with big dreams, who’d tried to build a championship golf course and a five-star resort, but couldn’t attract enough investors. The two men were equally ambitious, and they each had a wife named Linda.

That spring, Baker was recovering from a terrible accident. The brakes had failed on his tractor and after rolling helplessly backwards down a hill, Baker had damaged his spinal column in a crash. On hearing of Baker’s misfortune, Jacobson arrived and offered to get him out of the house. Baker feared he would never walk again, but Jacobson was insistent. He helped his friend into the car, and they drove up into the mountains.

When Baker first found out that Jacobson controlled the McDonald’s Monopoly promotion, he had mixed feelings. “Well, in 1985 we lost our home,” he explained. “Our family had five children, and…for the last several years we’d been, as a family, chasing these game pieces to… have a little hope of winning one of them.” Baker’s companies owed nearly $30,000 in back taxes, and county tax officials had started to sell parcels of his land at auction.

“Let me give you hypothetical,” Jacobson said suddenly. “If I were able get a game piece, do you know someone who you trust that would cash it?”

“Are you serious about this?” asked Baker.

He said he’d need to think about it. But Baker soon realized a windfall would ease his financial woes. Soon, Jacobson handed him a $1 million game piece. Whoever redeemed it, he instructed, would have to say they pulled it from a hash brown bag. This time, Jacobson wanted $100,000, the biggest kickback he’d ever demanded. “He was a friend,” Jacobson recalled. “I thought I could trust him.”

“George, you’re not going to believe this,” whispered Baker, leaning over a Waffle House table in Seneca, South Carolina. “But I was at breakfast with a friend of mine and he pulled off this winning game piece.” George Chandler, 30, was the owner of a successful plastic injection company, and Baker’s foster child. Chandler was a teenager when Baker took him in. “One day he showed up on our doorstep with tears in his eyes,” Baker recalled. “His momma had just thrown his clothes out in the middle of the yard because he helped his sister go to Georgia get married.”

Baker showed Chandler the winning game piece in a tiny Ziplock bag, and offered to sell it to him for $100,000. Baker explained that the winner was going through a divorce and didn’t want to split his McDonald’s winnings with his wife. (Or that was his story.) Chandler could only come up with $50,000, but on June 6, 2000, Baker helped him fill out the McDonald’s claim form. They photocopied the game piece and mailed it off to the redemption center. Baker warned him four times not to participate in any promotions, but on June 26, his telephone rang.

“You need to be up here at South Union McDonald’s at eleven 0’clock,” Chandler said casually. McDonald’s was presenting him with a giant check, he said. Baker was incensed. “There’s more to this than you know,” he hissed. But it was too late. When Baker arrived at the McDonald’s restaurant, two TV news crews were filming Ronald McDonald showering Chandler with confetti. That footage found its way to the FBI field office in Jacksonville.

In March of 2001, the McDonald’s promotion started again, with a “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?” promotional game. “That’s where the real greed on my part came,” Baker admitted. He asked Jacobson if he’d accept a plot of land in Edgewater Hills for a couple of game pieces. Baker gave a $1 million winner to a friend, Ronnie Hughey, and a $500,000 winner to his wife’s sister, Brenda Phenis. He gave them strict instructions on how to set up fake lives in other states, claim their prizes, and keep their mouths shut.

On April 27, 2001, Dent received a call from McDonald’s, informing him that a Mr. Ronald E. Hughey, a lifelong resident of Germantown, Tennessee, had claimed the $1 million prize. When Amy Murray called Hughey’s phone, she asked him to appear in a TV commercial, but Hughey said he’d prefer to remain anonymous, because he was suffering from depression. Technical agents soon discovered that Hughey’s Tennessee telephone number was just a call forwarding device. He actually lived in Anderson, South Carolina, just miles from the home of George Chandler, the latest winner.

To conceal his sister-in-law’s South Carolina address, Baker took Brenda Phenis on a road trip to North Carolina, he recalled. “She had located an apartment, had rented it, obtained a phone, a mailing address, bank account, and I think a North Carolina drivers’ license.” On May 16, 2001, Baker stood over Phenis’ shoulder as she dialed the McDonald’s hotline and claimed the $500,000 winning ticket. Phenis had agreed to pay the taxes, give Baker $90,000 and Jacobson $70,000, and keep $90,000 for herself. “She had made commitments to other people that she was going to buy them a car, build a house, and she overcommitted,” recalled Baker. Phenis also told her son about the scheme, and his wife, and her other sister.

On May 30, 2001, McDonald’s notified Dent of Phenis’ $500,000 win. He checked the credit bureaus and quickly discovered that she too lived in South Carolina, in a town called Westminster. Dent found a map of the state, and pinned the addresses of Hughey, Chandler, and Phenis. He had uncovered a 25-mile golden triangle of suspicious McDonald’s winners, and at its center was the lakefront home of Jacobson.

Dent requested that McDonald’s delay sending checks to Hughey and Phenis while he applied for wiretaps. “This intentional delay…proved very fruitful,” he recalled, because three weeks later everyone was panicking. On recorded calls, Jacobson told Baker that Phenis needed to insist on “something in writing” from McDonald’s so Baker could make a “legal issue” about the delay. “I’d say… ‘do we need an attorney or do I need to call the home office’” Jacobson suggested, “or do I need to call Burger King?”

“That’s right,” agreed Baker. But deep down, he had a ‘gut feeling’ that they’d been caught. “I felt the eyes,” he told me.

Phenis, too, was feeling the pressure. She confessed to her pastor and stopped answering Baker’s calls. He feared she was going to keep the entire check for herself. Dent listened to Baker’s tense phone calls with his wife. Baker said that if Jacobson knew that Brenda had gone rogue, he’d report the ticket stolen and say he was threatened to hand over the game pieces. Baker decided that Phenis should give him the money, otherwise he’d have to “raise his hand” himself, and have the U.S. Marshals arrest her. “I want it all,” Baker told his wife. “No if, ands, or buts about it.” He raced to Phenis’ fake apartment where the check was due to arrive. When he opened the door he found the light on and the air conditioner humming, but no one was in. On the floor he found a tear-off strip from a FedEx envelope.

Baker called his wife, and gasped: “Brenda’s running with the money.”

Time was now ticking for Dent and the FBI. On July 11, they would launch their second and last promotional game of 2001. Knowing that the game was compromised, Golden Arches executives considered canceling the whole thing. But Dent insisted he needed one more game to gather enough evidence. Jack Greenberg, the McDonald’s CEO, had a big decision to make. To run the game knowing it was corrupt could invite lawsuits and damage McDonald’s reputation. His company had endured a rough year, with a scare over mad cow disease diminishing European sales, and the brand’s domestic business was in a funk. “I had to do what was right,” Greenberg later told the Chicago Tribune. “If you’re sitting in my chair, I think you’d do the same thing.”

Backed by a massive promotional campaign, in July McDonald’s launched the “Pick Your Prize Monopoly” game. Restaurants nationwide were decorated with Monopoly rooftop banners and drive-thru decals. Diners couldn’t escape Rich Uncle Pennybags, who peered out from tray liners and even garbage cans, urging them to play. McDonald’s distributed 57 million paper game boards in Time, People and Sports Illustrated, while radio commercials whipped up interest in the two $1 million prizes, payable in “cash, gold, or diamonds.”

But the two winning game pieces were already in the hands of Jerry Jacobson.

He gave one to his trusted recruiter, Glomb, putting the former drug trafficker on the FBI’s radar for the first time, and the other to Baker.

“I got to have some kind of deposit,” Jacobson told Baker, in a phone call recorded by the FBI.

“My word’s not good enough, huh?” said Baker.

“Your word is good,” Jacobson said. “Are you willing to back it up, though?”

“Yeah, I’ll back it up.”

Baker had other problems. His sister-in-law Phenis had flown to California to receive her $500,000 prize directly from Simon Marketing. Baker and his wife had spent days staking out the Indianapolis International Airport, watching every incoming flight for her return. On July 20, when Phenis finally strolled into arrivals, the Bakers accosted her and found she had $20,ooo in cash and a cashier’s check for $480,000. Their tense confrontation was filmed by an undercover team of local FBI agents.

Driving to a quiet corner of Corbin, Kentucky, Baker handed Jacobson a McDonald’s paper bag containing $70,000 in cash, as payment for the next winning ticket. Baker planned to pass the ticket to his last winner, Ronnie Hughey, who had recruited “his man in Texas” to win. Listening in to their call, Dent ran his finger down a list of numbers recently dialed by Hughey. The only Texas number belonged to Hughey’s brother-in-law, a construction manager in Granbury named John Davis.

On Sunday, July 22, at 10 a.m., two FBI surveillance teams tailed Baker and Jacobson to a secluded area in a South Carolina town, ironically named Fair Play. But the dense, woodland area prevented them from witnessing the transfer. Agents then followed Baker to Hughey’s home in Anderson, where they believed he passed him the $1 million winning game piece. Eight days later, Dent received a call from Amy Murray. Someone had claimed the $1 million, she said. Dent interrupted her. He asked if the winner’s name was John Davis.

Yes, she said.

“From Granbury, Texas?”

By giving the go-ahead to run the game, McDonald’s CEO Jack Greenberg had allowed the feds to discover Glomb and his network of million-dollar winners. “I would do it again,” Greenberg said. “What we found out allowed the FBI to complete its investigation.” Knowing that juries are convinced by splashy stings, the FBI asked McDonald’s to help them trap the suspects. Together with Amy Murray, they cooked up a plan to invite every corrupt winner to Las Vegas for a “winner reunion,” where the FBI would bust them all at once. But they decided against the idea. It was just as effective to shoot fake McDonald’s commercials, trapping Glomb’s final winner, Michael Hoover, at his home in Rhode Island.

Nineteen days later, on August 22, 2001, the FBI fanned out and made eight arrests, including Dwight and Linda Baker, John Davis, Andrew Glomb, Michael Hoover, Ronald Hughey, and Brenda Phenis. In a pre-dawn raid, FBI agents surrounded Jacobson’s red-brick home, crept up the garden path and knocked on his door. A shocked Jacobson was taken away in handcuffs and charged with conspiracy to commit mail fraud, his bond set a staggering $1 million. Staff at Simon Marketing were left in disbelief. How could the man who searched their shoes be guilty of theft?

The arrests created a media sensation, and Attorney General John Ashcroft told the press: “Those involved in this type of corruption will find out that breaking the law is no game.” Americans were shocked that McDonald’s customers had been duped for so long. Jeffrey Harris, a former Deputy Attorney General, complained to CNN: “People that were buying the hamburgers, all they were getting at this point was cholesterol.” Meanwhile, Jacobson became the butt of the media’s jokes: “Are you worried the police are going to take him down the station and give him a grilling?” one newscaster asked. “I’m sorry, I couldn’t resist.”

During his six-hour interrogation, agent Dent presented Jacobson with their evidence. For over 12 years, Jacobson’s scheme had existed only in his mind. Now his crooked plan was a chart on FBI stationery. But Jacobson still thought he had his “ace in the hole.” In the weeks that followed, he provided the FBI with documents he claimed proved that Simon Marketing rigged McDonald’s contests to bilk Canadian customers. A source close to Jacobson told CNN that he also hoped to use his St. Jude’s million dollar donation to try and score a reduced prison sentence. But investigators believed he mailed the game piece to the hospital as “a lark,” after failing to recruit a winner in time for the contest deadline. (Jacobson declined to be interviewed for this article. Most of his story comes from court documents.)

With each of Jacobson’s nine charges carrying a five year penalty, investigators warned him he’d be 104 on his release date. “I wouldn’t be getting out,” he told them, because he had multiple sclerosis. In exchange for a signed confession and his testimony in court, Jacobson pleaded guilty to three counts for a total of 15 years. The government also took everything he owned. Back in Lawrenceville, his neighbors watched as agents drove away in his brand new Honda S2000 sports car, and other vehicles including a luxury Acura, a minivan, and an ’86 Chevy El Camino.

McDonald’s CEO Jack Greenberg told the country in a television address that the company had immediately terminated its relationship with Simon Marketing. In Los Angeles, staff silently packed up their desks as the company dissolved. “McDonald’s is committed to giving our customers a chance to win every dollar that has been stolen by this criminal ring.” Greenberg said later, in a somber television commercial in which McDonald’s unveiled a special $10 million instant giveaway, and asked for a “second chance.” To ensure winners were truly chosen at random, there were no game pieces or prize boards. Instead, a prize patrol tapped random customers on the shoulder. McDonald’s, who declined to comment for this article, also quietly honored the $1 million prize sent to the hospital, which was spent on treatment for kids battling cancer and other terminal diseases.

The colorful court case, held in Jacksonville, Florida, started September 10, 2001, the day before terrorists crashed planes into the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and a field in Pennsylvania. The stunned news media quickly forgot about the McDonald’s trial, which explains why so few Americans remember the scandal, or how it ended. During the trial, jurors watched defendants celebrating in McDonald’s commercials, including the fake one filmed by the FBI. Glomb recalled that the victim of the McSting, Michael Hoover, told him that he thought Amy Murray “kind of liked me,” before learning she was part of an FBI operation.

More than 50 defendants were convicted of mail fraud and conspiracy. Jacobson’s “super-recruiters,” Schwartz, Hart, Couturier, and Glomb were sentenced to a year and one day in prison, and handed huge fines. Baker recalled that one of the FBI’s top agents, known as the “human lie-detector,” interrogated him, and added that if the FBI had focused on surveilling terrorists not McDonald’s winners, 9/11 might never have happened. Baker, who was excommunicated from the Mormon church, his wife Linda, her sister Brenda Phenis, and the dozens of other “winners” received only probation and are still paying back their prize money at $50 a month. Four winners, including Baker’s foster son, Chandler, had their convictions overturned by an appeals court, who agreed they were duped by recruiters.

Richard Couturier, who was sleeping in his car at the time of the trial, told the court that a man he believed was in the Mafia warned him not to mention Don Hart’s name to investigators. He said he feared getting “whacked.” Then, just before the judge announced her sentence, Robin Colombo caught a glimpse of her lawyer’s paperwork, and saw she was going back to prison. She screamed and made a desperate dash for the exit, and reached an outer corridor before marshals overpowered her. She was sentenced to 18 months. Behind bars, she discovered the Bible and wrote her life story, From a Mafia Widow to Child of God. She was later reunited with her son, Frankie, who did not join the mob.

Jacobson took the stand dressed in a blue golf shirt, looking tired and gray. One attorney described him as “a gigantic master criminal,” before he admitted to stealing up to 60 game pieces over a dozen years, totaling over $24 million in prizes. “All I can tell you is I made the biggest mistake of my life,” he said quietly, before agreeing to pay $12.5 million in restitution. The judge sent him to jail for 37 months. He did not pass go. But before leaving the court he shook hands with the man who brought him to justice. Perhaps Jacobson saw in Richard Dent the man he could have been, a steely-minded detective. Dent, who declined to be interviewed for this article because he does not speak to the media, quietly returned to his work on white collar crime, and is now retired.

McDonald’s sued Simon Marketing, who counter-sued. A group of Burger King restaurants tried to get a class act lawsuit together, so did a group of unhappy McDonald’s customers in Canada. The Monopoly game had demonstrated the evils of chasing riches at the expense of others, but the saga also proved that strange things happen when people conspire to cheat fate. Gennaro Colombo won a car using a stolen prize ticket and died in a car wreck. And when lady luck regained control of the McDonald’s competitions, she handed winning tickets to a man wearing a full Pizza Hut uniform; a Taco Bell owner; and a former homeless man who was later charged with beating up his fiancée–a PR nightmare.

An audit of newspaper archives from Jacobson’s reign turned up some other, interesting “wins.” In 1986 a cop in Florida struggling with unpaid bills told reporters how he found a winning McDonald’s game piece in his squad car. A year later, a family living just 43 miles from Jacobson’s home won $250,000. Then there’s the “imposter” M&M candy, like the one in Robin Colombo’s freezer. In 1997, a newspaper reported that a college student in Florida won the $1 million prize, somehow finding the gray-colored M&M before Mars even announced the contest. The boy’s father, a Baptist, said that if his son had spent his money on a lottery ticket, he would have been sinning. “The Lord doesn’t approve of gambling,” he said. “But a candy contest is something different.” The winner and his family did not answer enquiries sent to their home in the Carolinas, not far from the golden triangle of Jacobson’s phony winners.

Not long ago, I spoke to Glomb, one of Jacobson’s “super recruiters.” He was philosophical about his conviction. “I’m not one of those people who are mad at [the FBI],” he said. “It was a game, and I lost.” Glomb says he still speaks with Jacobson, who is 76 and in poor health, but living a quiet life in Georgia. “I hate to say it but I’d probably do it again for the same reason,” Glomb said, rakishly. “Every time I talk to Jacobson, I always tease him, I say, ‘You got any tickets?’”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.